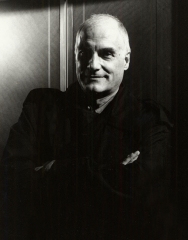

“The Joyous Pessimism of Barbet Schroeder”

Interview with the director of ‘Kiss of Death’

– by Gavin Smith

In an era when mainstream cinema is increasingly the domain of impersonal efficiency – sensibility as inadvertent by product of technocentrism – European directors in Hollywood have something to offer that ought to be increasingly valuable: a different cultural and aesthetic perspective. Yet, ironically, most of the Europeans now thriving in the U.S. have mastered how to make American movies, only more so. Paul Verhoeven, Wolfgang Petersen, Renny Harlin, and even George Pan Cosmatos, Roland Emmerich, and Uli Edel aren’t sellouts – they’re doing what they always set out to do. Those following the more fraught, Louis Malle route – attempting to apply their personal voices to relatively modest enterprises – are few: Lasse Hallstrom, Agnieszka Holland, Percy Adlon.

Barbet Schroeder is the only European well established in the U.S. to have achieved a measure of balance between Hollywood’s commercialism and his own philosophical agenda. Compare him to Paul Verhoeven: Both filmmakers only fully engaged with genre in the U.S. phases of their careers, and both have reputations for an interest in the perverse and the provocative. Verhoeven has settled into a high-concept niche, directing big-budget, stylishly opportunist exploitation, content to play with Hollywood’s limitless potential for more or less mindless spectacle and sensationalist excess. Schroeder by contrast has made notably thoughtful, enigmatic, personal films, on smaller budgets, always within a coherent, unifying perspective and in thematic harmony with his European phase.

He has had other European emigres at an advantage for several reasons. His first American films were semi-independent (Verhoeven’s have all been with major studios). His background in the French New Wave – producing for directors Eric Rohmer and Jacques Rivette – as well as his diversification into documentary in the Seventies allowed ample time for his creative identity to coalesce. And his transition to America was more extended than most: he struggled to make Barfly for a number of years, during which period he could surely have accepted other offers from Hollywood.

While Reversal of Fortune might be considered a courtroom drama and Single White Female a psychosexual thriller, Schroeder’s sardonic moral ambiguity and teasingly metafictive constructions prevailed over genre without entirely subverting it. His new film, Kiss of Death, is a contemporary crime thriller in which an embittered car thief determined to go straight (David Caruso) is coerced by a politically ambitious DA into infiltrating and informing on a car theft ring in Queens, New York. It finds Schroeder edging still closer to genre – yet nevertheless withholding moral schematicism and cathartic heroic triumph. At the same time, he delivers a film informed by his characteristic preoccupations with transgression of social norms, sadomasochistic power dynamics, and the depiction of a subcultural milieu.

His career has been distinguished by collaborations with three notable European DPs: Nestor Almendros from More (’69) through Koko, the Gorilla Who Talks (’78), Robby Muller for the key transitional films Tricheurs (’83) and Barfly (’87), and Luciano Tovoli from Reversal of Fortune (’90) onward. Over the years Schroeder’s visual style has evolved away from documentary aesthetics and an observational, nonemphatic mode toward a more elegant, smoothly sculpted mise-en-scene and a greater sense of pictoralism in the interaction of movement, color, light, and space. At a formal level, from its opening crane back through a car-wrecking yard, Kiss of Death represents his most accomplished and controlled film yet, and his most classical. At the same time, his m.o. is essentially the same, particularly in terms of the central importance of his vivid sense of place. (The first film he produced, the compendium Paris vu par. . ., was conceived as a series of episodes originating in specific Paris neighborhoods.)

If Schroeder’s films can be said to share a common impulse, it is toward examining the moral and philosophical consequences of extreme forms of extra-social, if not antisocial, freedom. The dropout or subculture mentality of each film is fueled by a hedonism or an obsessive craving that threatens to destroy its communicants and jeopardize their very identities: heroin in More (which could be the title of every subsequent Schroeder film), the quest for an undiscovered paradise in La Vallee (’72), s&m amour fou in Maitresse (’76), professional gambling in Tricheurs, drinking in Barfly, the assumption of another person’s identity in Single White Female (’92). All invite breakdown, yet also offer the promise of liberation and renewal. Throughout, Schroeder’s interest lies in laying bare the contradictions between humanity’s high functions and its basic instincts.

In particular, in Maitresse and the extraordinary, little-known Tricheurs , Schroeder constructs scenarios of unparalleled excess. In Tricheurs, a career gambler (Jacques Dutronc) initiates a neophyte (Bulle Ogier, Schroeder’s longtime collaborator and wife) into the hermetic, ritualized universe of the international casino circuit, while the film metamorphoses from absurdist existential/metaphysical drama into suspenseful crime caper and back again. In Maitresse, a dominatrix (Ogier) and a small-time thief (Gerard Depardieu) meet cute when he breaks into her torture chamber, fall in love, and gradually negotiate their way to a viable relationship. In fact, the s&m, mentor-student power dynamic may be the paradigm for human relations and identity in Schroeder’s later films, up to and including Kiss of Death and crook-turned-informer Kilmartin’s masochistic subordination to personifications of both law (Samuel L. Jackson’s mutilated cop) and crime (Nicolas Cage’s maniacally bulked-up Little Junior). – G.S.

, Schroeder constructs scenarios of unparalleled excess. In Tricheurs, a career gambler (Jacques Dutronc) initiates a neophyte (Bulle Ogier, Schroeder’s longtime collaborator and wife) into the hermetic, ritualized universe of the international casino circuit, while the film metamorphoses from absurdist existential/metaphysical drama into suspenseful crime caper and back again. In Maitresse, a dominatrix (Ogier) and a small-time thief (Gerard Depardieu) meet cute when he breaks into her torture chamber, fall in love, and gradually negotiate their way to a viable relationship. In fact, the s&m, mentor-student power dynamic may be the paradigm for human relations and identity in Schroeder’s later films, up to and including Kiss of Death and crook-turned-informer Kilmartin’s masochistic subordination to personifications of both law (Samuel L. Jackson’s mutilated cop) and crime (Nicolas Cage’s maniacally bulked-up Little Junior). – G.S.

Kiss of Death was announced as a remake of Henry Hathaway’s 1947 film, yet there aren’t any really solid shared elements.

One is maybe the shadow of the other one, but that’s all you can say. A vague shadow. I wanted to change the title, call it “The Taste of Metal.”

The world you put onscreen here has never really been captured before. At least, not convincingly.

Yeah, this is really the ordinary level of car thieves’ daily lives in Queens. It’s not the top and it’s not the bottom – it’s the middle level.

I wanted to do a movie with Richard Price for many years, and hoped that one day he would do a script I’d feel comfortable directing. It happened with this one; [from] the first draft I felt very excited. He had done a lot of research into the world depicted in the film, and that’s always invaluable. To get excited by a movie, I have to feel the reality of the story, not only in the characters but also in what happens; [it must be] real and documented on every level. Also, its world was not a world of good guys and bad guys. This is a film noir where everybody’s gray. That ambiguity attracted me enormously.

There’s an underlying feeling of repression: imprisonment, deception, violence, played out against this world that has a topless dancer club as its central hub, a place where sex as spectacle reinforces repression. The film and its main character are curiously asexual.

It’s something that comes very often with the street, this form of repression mixed with violence. It’s true of both Little Junior and Kilmartin.

Is this a world you’ve ever entered?

Yes, often. When I was doing Tricheurs I met a lot of guys in France who did similar jobs to Little Junior. They had all done time or were going to. They were very nice and at the same time very scary. Some were killers. Some were specialists in debt collection: If you owed somebody money, they would call those guys, who would take you in a truck and circle around town and torture you until you agreed to pay; then they drive you to the bank, you write the check, and then they leave you. So they had a nice side, and another side that was utterly disgusting.

How do you meet such people?

Through different friends. This is never any problem. You meet one person, they introduce you to another.

Aren’t you in a strange position in such situations, as an outsider?

I hate to feel that I’m an observer or a voyeur. I always consider myself exactly the same.

Isn’t it dangerous for you?

It’s scary if they have a problem with you. There was no reason why they would have a problem with me. Of course if you’re with such guys and suddenly they think you’ve betrayed them. . . . When I was filming General Idi Amin Dada [’74], if someone had planted a bomb – which had happened many times – and I was suspected, it would have just been a bad accident.

Little Junior is a wonderful creation. Nicolas Cage really goes to a new level.

Yeah. Not an obvious casting choice. For me it was, but I was alone. At the time, nobody believed me.

Were you conscious of the similarity between Little Junior and Idi Amin – both endearing childlike psychopaths?

[Chuckles.] Absolutely, yeah. I got along great with Idi Amin. But I wouldn’t get too close to him. I wouldn’t go to dinner at his home, although I was invited. I had to draw the line.

How did you get him to trust you?

It was straightforward. I said I was working for French TV, that I wanted to do a portrait of him and he should tell me what to show, that we were going to do this together. I consider him co-director because he had many of the ideas.

Was it his idea to use actual army maneuvers to demonstrate how he planned to invade Israel?

Oh, absolutely. How could I come up with that? The more I empowered him with responsibility for the movie, the more he got caught up doing it. One of my favorite shots is when he had organized a takeover of the Golan Heights, and this helicopter comes, and the camera is on him and he says, “Film the helicopter!” and points up, and the camera pans to the helicopter. [Laugh.] Wonderful.

In a 1977 interview you spoke of how the distance between the camera and what it films is of central importance to your approach.

It still is.

In your American films I see a definite relaxation of that tension between observing action and influencing it. The camera seems more intimate with the action.

I’ve done movies that were more dramatic, like Single White Female, where camera movement can be part of a building-up of tension. But the problem of distance is exactly the same for me. That’s why I don’t do many sizes in a scene; I don’t do a version very close, another medium-close, and another wide. I try to find exactly the right distance for that moment.

Does that mean you restrict the ability of the studio to recut things?

My dream is to be like John Ford, who filmed only exactly what he needed. I can’t really achieve this ideal because it would be detrimental to the actors. An actor has to play the whole scene, so if you need a closeup for a phrase, you end up playing everything that comes before it. Ford [did it his way] because he came from silent film.

Do you like to do a lot of takes and build things, or rehearse until it’s ready and then just shoot it?

Depending on the actors. On Tricheurs I had Jacques Dutronc, an extraordinary actor on the first take, like Michel Simon, but after that it just never would be as good. And opposite him I had Bulle Ogier who would be good after three or four takes. It was pretty complicated, managing a situation like that.

who would be good after three or four takes. It was pretty complicated, managing a situation like that.

But usually I work with actors who like to do a few takes. So basically, when I have two takes I consider good, I say, “Okay, we do one now just ‘for the pleasure.'” And I encourage the actors to do exactly what they want, no pressure whatsoever, because we already have what we need, let’s see what happens. And one time out of five it becomes the take that’s in the movie. That’s what a good movie is – when you go beyond what was planned and you surprise yourself. That is the drug. You go from surprise to surprise.

When the film is finished and screened, are you drawn into is illusion of narrative or do you just see the residue of seventy days working with actors and crew?

I only remember the shooting of something when it doesn’t work.

So the fantasy you create still seduces you – you believe it.

Oh, absolutely. When I see the first assembly, it’s always a very painful moment because it doesn’t fit, it doesn’t correspond to what’s in your head, what you were hoping [for]. But soon you find a few things that were preventing you from entering the movie as you dreamed, and you fix it little by little. You know you have great performances, but the maximum is not yet there on the screen, it’s interrupted by the cuts or something like that. . . .

Every film you’ve made seems dominated by a central location or milieu. In Kiss of Death, the strip club Baby Cakes sort of casts a shadow over everything else.

Every movie is some kind of documentary about a location and the people who inhabit it – whether they are torn apart by it or are comfortable in it.

Was Baby Cakes a real location or a set?

A real club that was just abandoned. It had ‘been functioning a few months before. We changed it a lot but the basic structure was the same. There is not a single scene in the film that was done on a soundstage – that’s one thing it has in common with the original film.

What did you have in mind in terms of visual style?

Obviously there’s still the noir element of an honest man fighting against dark forces, so we tried to see what the equivalent of a noir movie would be today. I didn’t want to do something neo-noir where you use the same vocabulary of shadows and all that. We paid homage to that in passing, but I thought you could obtain the fantastic or surreal quality of noir by being extra-real and extra-sharp visually; you would obtain the dream through hyperrealism. Thanks to [cinematographer] Luciano Tovoli, we tried to have something that is three-dimensional, [with] the maximum depth of field. I really don’t like telephoto lenses, anything above 50 or 75.

When designing a scene, is there a key shot around which everything else fits?

Yes, of course, and there’s always the point that you want to get across. But first of all you have to get the scene. In order to get the scene, the actors have to feel comfortable with it. You can’t start with your important shot and not have the actors know what the scene is about. So you rehearse without thinking about the shots, just for the actors to have the reality of the scene. And only then do you explain why you need them to be at a certain place at a certain moment, and to pose a little bit because you need to cut there because the shots go in a certain order. It’s dangerous to reverse the process – the actors can get lost.

In a given script, are there one or two scenes or moments you feel very strongly about and visualize very specifically?

More than one or two. There are many things I see very clearly, but when somebody comes up with a better way to do it, I jump on it. Visually, the whole ride of the trucks and the arrival at the harbor with the boat was really important to me. And the murder of Omar [Ving Rhames]: I had every single shot in my head from the beginning because it was very tricky – it’s a totally unbelievable thing that you had to make believable through the juxtaposition of shots.

Because Little Junior has to cross through his field of vision.

Exactly. If you don’t shoot it right, it can look ridiculous. This was really a scene that was about camera position, shot sequence, and shot length in order to confuse and surprise the audience.

Sometimes you have arguments with actors who are always looking for the truth in acting and don’t understand that the camera has its own truth. [In another scene], David Caruso is surprised by a dog in a car he’s about to steal; he has to [retrieve his break-in tool], but he’s afraid because the dog is just an inch away. To shoot his face while he’s doing that, obviously you have to put the camera in a very strange place. He’s reaching left of the camera and he’s supposed to act something that during shooting looks very weird. There was a lot of argument; Caruso thought it was totally absurd, ridiculous. In the end the result is perfect.

On Reversal of Fortune there was a scene where I told Ron Silver [as Alan Dershowitz] to whisper to his companion that things were going well because the judge had just made a mistake. Ron wouldn’t do it. I said, “Why?” He said, “Because I’m afraid the judge would see me.” I said, “The judge would only see if I put in a shot of the judge just before that shot.” This kind of argument can be endless and really goes to the essence of filmmaking.

At the same time, I totally understand actors who want everything completely true for them to be able to perform – to be in a true place in their heads. I’m like that as a director. I couldn’t do a period piece, for example, because for me it would cost millions: I would need to feel that everything was true. If I do a period piece I’ve got to be pretty deluded to think that I’m in reality. If I’m on location or on a very good set, I can believe that.

Single White Female was the only film where you did a lot of soundstage work?

Yes. The whole thing was designed for a certain effect of suspense. I like that film very much; I was very disappointed when critics said, Oh another film like. . . they put it together with a series of movies. . . .

You mean Fatal Attraction?

Fatal Attraction was the mold for many other movies, including Single White Female.

A lot of women I know liked your film.

It touched something I’d observed in real life many times, a woman taking on another woman’s identity, and that’s what convinced me to do the film. I knew this phenomenon was real. At a certain age when personality is not fully formed, since appearance is very important, girls may decide to appear like a woman they admire. Sometimes they end up speaking the same way, using the same words. And then of course with age they become themselves.

It’s also part of a pattern of student-teacher relationships that run through almost all your films.

It’s something that’s important to me, but it was not conscious.

Single White Female reverses the model: the teacher doesn’t want to teach –

– right, the student forces the teacher.

With the interchangeable identities and haunted-house setting, it could also be seen as a remake of Jacques Rivette’s Celine and Julie Go Boating (’74), which you produced and acted in.

[Laughs.] Since Celine et Julie, which is such a masterpiece, is about movies and storytelling, if you take two women and put them in a movie with a fantastic element, with mystery and suspense, you can always start speaking about it.

Do you feel your work as a whole articulates a philosophical perspective?

For me, philosophers and artists divide themselves into two camps. One thinks human nature is intrinsically good and just needs a little help to express its goodness; the other expresses more or less the opposite. I definitely believe we shouldn’t have any illusions about the essential goodness of human nature. Also, that leaves more room for irony.

The most generous and warm film you’ve made is probably Barfly.

Because that is the movie and the writer closest to what I am philosophically, and Barfly shows that this view of the world doesn’t prevent being generous or joyous. That’s why I’ve always called myself a joyous pessimist.

What was the purpose of The Bukowski Tapes (’85)?

I was doing a little bit of an Idi Amin Dada with him, except that I was not dealing with a monster-killer, just a monster-writer – and somebody I loved completely, without restriction. I just wanted him to take off and do some of his speeches. But to spend an evening with Bukowski was never to spend an evening hearing somebody pontificating alone. He would start on an anecdote, an aphorism, whatever, but then ask other people to contribute; he would always try to include everybody – and people were not always up to his level.

I tried to just excerpt his thoughts. When I was editing I was so excited: I thought I had invented a new form, a collection of filmed aphorisms, 50 speeches of three minutes each. Fifty little bits that were self-contained and about something – a consideration of beauty or of pollution, say – and they were all extremely funny. For me, it’s a great work and a unique document about Bukowski. It’s more than a documentary; there’s a strange, mad energy in those tapes. Even he was astonished when he looked at it.

Did you shoot them yourself?

There was a group of us, [we] took turns at the camera – and we were drinking with him, so it’s not very well framed. It was filmed on one-inch video, very high quality. It’s on sale by mail only because, unfortunately, you can’t get that kind of product into videostores.

Did Bukowski represent a kind of teacher or mentor to you?

Definitely, yes.

So you must have approached Barfly very differently from your other films – you weren’t just trying to satisfy your own artistic vision, but somebody else’s, too.

Right. I wanted to make a movie that was as much his as mine – or even more [his], the more the better. Before, I was writing screenplays or outlines, bringingin writers to help, piecing together screenplays that were my original ideas. They were auteur movies that were not completely written by me. Bukowski was extremely liberating because at night when I knew a scene was not working, I had someone I could call who could come up with the solution ‘just like that [snaps finger].

If there was a creative difference, did you defer to him?

I don’t remember anything like that. I told him he was welcome on the set every day. He said something that really touched me: “No, because you have to do this movie. It has to come from you. If I’m there too often, it won’t help.” So he only came three or four times.

His script is far more romanticized than his other writing.

It is not romanticized – it is a real, great love story.

While his books and short stories were all written like screenplays, at the very end the punchline would be completely literary and there was no way to find the equivalent in the movies. That’s why we ended up doing a movie about a period of his life he had not written about. Like all Bukowski’s work, most of the stuff in the movie really happened, and then it’s improved by a mysterious twist. In this case there is the improvement that is inherent to filmmaking, because in film you have to tell a story and organize a little. I didn’t organize too much, but in order to make it move I had to add a few elements and change a few things. All the best scenes were perfect right from the start.

Why did you chose to open the film with the camera entering the bar and moving through it, and then end with the same movement in reverse?

It was a wonderful ending. Life was going on. It was the best way to indicate that nothing had changed, he hadn’t taken this opportunity that was handed to him to become a successful writer, he had chosen life and love.

Like every filmmaker, I’ve encountered problems with endings. With Barfly I knew from the start I had the perfect ending and the perfect shot for it. That is very, very liberating.

My obsession in life, one of my all-time fantasies, was to be able to become someone else – to walk through walls, to be in any social milieu, to be able to move from here to there. When I was 14 I was so obsessed with being able to go into buildings where people lived and see their places that I became a soap salesman, knocking on doors, selling soap for the blind. (I used it in Maitresse: Depardieu and his friend are selling books door to door.) Another thing: I would never ever have a tattoo, because a tattoo would mark me and I could not become someone else! So to work with a great writer was liberating because I could try to become him a little bit, try to do what he would have done if he was doing the movie. That way, I don’t have to deal with myself – and that’s always very good. [Laughs.]

What you say about wanting to be free to go anywhere – that’s what cinema is about, that’s what the camera is able to do.

Yes, absolutely, but I did it first without even a [still] camera. When I was 18, I [went] door to door in Calcutta with the Communist Party, going into people’s houses trying to convince them to vote for the Party. Although I was not a Communist [chuckles]. I have practically no photographic record of those important travels; I thought a camera would prevent me from living those moments to their fullest.

You must like location scouting. Or have you got it out of your system?

I still enjoy it, yeah.

What larger need does directing satisfy?

[I once answered a questionnaire]: “Pour en savoir plus – To know more.” Meaning to explore, to find out more about others, myself, the world, about cinema itself. That was the answer and I think it’s still true.

There’s Bulle Ogier’s line in Maitresse: “It’s wonderful to be able to enter people’s madness insuch an ultimate way.”

[Chuckles.] Well, that’s definitely a line from one of my movies.

Reversal of Fortune, to me, is a film about the unknowable nature of truth and the implications of that morally.

My ambition was to have the audience split 50-50 at the theater exit and arguing over what happened – which from the point of view of Von Bulow was a big gain, because before the movie was made everybody thought he did it. And I was very sensitive to the humor and irony linked to the fact that you don’t know. So for me it is a comedy of manners, a strange comedy. For me, Barfly was also a comedy. Hopefully one day I’ll do a comedy that’s not in the closet like those two.

With its different versions of the truth, it again raises the spectre of your old collaborator Rivette.

Actually, if you’re talking about Celine et Julie, [there’s also a formal relation]. You have a level of reality with Dershowitz and his students where they are trying to find things out, which is almost a documentary level. And then suddenly there is the fiction: whenever you’re in the Von Bulow, house, this is not supposed to be real, this is Claus’s [Jeremy Irons] version, this is a Hollywood movie, a Douglas Sirk melodrama – the style of photography, the music, everything tells you you’re in a fictional world. And then you have another, even more fantastic world, the world of Sunny Von Bulow [Glenn Close]. So there are three different styles in the movie. Whenever Sunny is talking, you have the Steadicam, which I don’t like usually but it gives you the idea of a floating soul above her body. It was great to play within three styles.

What stylistic ingredients went into that middle-level movie reality?

What I wanted to do, but couldn’t because of the cost, was to have, say, the curtains a different color in the maid’s and Claus’s versions of the same events. Since music is a very important element of a movie-movie, there is no music at all in the rest of the film except source music. It also meant camera movements that were not always justified by somebody moving. The camera was a little more godlike.

What was your opinion of Von Bulow’s guilt or innocence? Were you as ambivalent us the film?

Yes. This is my line: I always thought he didn’t do anything. But you can interpret that any way you like [laughs]: he didn’t do it, or something happened and he didn’t call anybody to tell them.

The last moment between Dershowitz and Von Bulow is extraordinary: Dershowitz has the line “Morally you’re on your own,” and you cut to the reverse of Von Bulow’s face with this strange expression as the elevator door closes. Was that an important, planned-out moment or was it discovered as you did it?

There were two moments like that. The other was when he gets in the limousine and says, “You have no idea,” and closes the door. Those were both images I had very early on.

Were they in Nicholas Kazan’s script?

Certainly not the one of the car. The other one I don’t think so either.

What inspired Maitresse?

I knew a woman who had been a very famous maitresse. She was kind of retired, but running this hotel all the prostitutes used to come to with their young customers, and she charged them very little. I would cook in the kitchen; I spent many evenings with her in that place, which at the same time was some kind of literary salon – there was Jean Genet and some publishers, writers, and they all admired this woman. She became a very close friend, and I kept asking her about all those crazy things she was in contact with when she was doing that work: “Were you ever in love? How did it affect your work, which was so much more demanding than the normal work of prostitution – dealing with the madness of people?” I remember taking Fassbinder there; he was very impressed by this woman.

Is it your most personal film?

Maybe. But I think it could be done better.

It’s the film that gave you a reputation – that has stuck with you – for being interested in the perverse.

Yes. I think it’s an extremely healthy movie myself. I really believe that it is joyous and life-affirming.

What’s the significance of the scene when Gerard Depardieu goes to the slaughterhouse and sees the horse killed?

That’s [when] he becomes a victim himself. Maybe it’s too heavyhanded, maybe I should redo this movie . . . . The idea was that he was confronted with this situation of being a victim or an aggressor, and he chose to identify with the victim by watching this slaughter and then going to a butcher and buying a horsemeat steak and eating it. It was a kind of primitive, unconscious ritual.

I interpreted it as an attempt to shock himself into a renewed awareness of his humanity: eating the horsemeat was a way of embracing the cruel side of human nature.

Yes. It works like that, too.

Maitresse stages a kind of negotiation between the urge to control and the need for submission or surrender.

It’s a love story where they finally find a way to do that. That’s why they end up driving the car [as they do]: both surrender, but both have control. As a director, you get tremendous satisfaction from observing and capturing reality, responding to it; but at the same time you are controlling or managing events. I think Maitresse is a very personal film in that it confronts that conflict.

This is a big dilemma because there is one thing I hate more than anything. I have a total, profound aversion to power, anything that expresses power. Casting especially is excruciating for me because you’re supposed to be selecting people right in front of their eyes. Walking among a group of extras, selecting ones for the scene – you feel like you’re in a concentration camp. Yet in the film-making process, if you don’t have the power to impose what you think is right, the movie is going to suffer. I just try to live with it, but do everything I can to make it less apparent and less painful – for me, and for the others.

How did Tricheurs come about?

Very simple. It’s gonna be the same story every time! I met someone. . . . I met the character in real life that Dutronc plays. He became a very good friend, then he was in jail, then he escaped and came to live with me in California for six months when I was [first] trying to do Barfly. During this time we talked about doing a project, and another friend wrote the story.

What’s he doing now? Still gambling?

Yeah.

Did he like the film?

I think so. Through this guy I discovered that the addiction of gambling was a strong drug, that it was very important because it plays a part in everyone’s life. Luck. If I should have a religion, I don’t believe in God, I believe in luck. The perversion of playing with luck in a masturbatory way, by gambling, is very frightening because it strips reality of all its romantic varnish. It’s almost a nihilistic practice where nothing matters anymore, especially money. I think it’s very healthy philosophically to have something that can clean your eyes and mind like that and give you a view of the world that may be closer to the truth. A very frightening world, but interesting. The idea that someone starts to cheat in order to go on gambling, and that whatever he wins through cheating he then goes to the other table and loses, and so on – I think it’s exhilarating.

I may have misread the film there – I saw a philosophical distinction being made between the person who gambles and is powerless and the person who cheats and thereby takes control of his life.

True, true, true. The movie plays with that irony.

The Dutronc character is morally repulsed by the idea of cheating at first.

Right, he never becomes a real cheater because he never profits from it. What’s your feeling about the ending, when they get all the money and buy the castle? Are they going to lose it all?

Of course. All through the movie he talks about the castle he wants to buy. He’s finally succeeded, he’s got it, everything is fine, and they go walking by the lake and see a boat leaving, and on the other side of the lake is a casino – and so they run to the boat. . . . So obviously they’re going to go on gambling and lose the castle.

[By the way, that was] one of my biggest horror stories of a location lost. I had the perfect castle, the image of his dream, an extraordinary castle by a lake. Just before shooting, the daughter of the owner, the man with whom we had the deal, died of anorexia. And before dying she said, “Please don’t let them shoot the movie in the castle.” I lost the location and ended up in this dinky little house, so all the grand irony at the end of the movie is lost.

The dialogue just before Dutronc and Bulle Ogier get on the boat, about a castle that doesn’t really exist, has a strange, metaphysical quality, suggesting that nothing is real.

Yes, that’s where gambling takes you. It’s a shame Tricheurs isn’t known here.

Unfortunately it [falls in] this in-between zone: art film or commercial movie? It opened at the Public Theater [in New York], got a fantastic review in the Times. But now only very few French movies get picked up for distribution in America, [unlike] twenty years ago, when more or less all the important French films came to the U.S. one way or the other, and you could feel what was happening. Now America sees only 1 or 2 percent of French productions – Colonel Chabert, whatever. It’s true not only of France but of every other country.

Have you ever reflected on the fact that you began in the French New Wave, worked many times with Rohmer and Rivette, and now you’re on Hollywood’s A list?

Never – I just move on and do what I like. [But] from the very beginning I knew about life and culture through American movies, before I knew anything about any other part of culture. I was watching three or four American movies a day, and almost nothing else except maybe Rossellini and Murnau, and Fritz Lang a little bit. My first film, More, was an American movie. I don’t feel so French because I didn’t spend my childhood there.

You felt out of place in France?

Oh yes. I was born in Tehran, spent a few years there, then went to Colombia, and that was where I grew up. I feel as much Colombian as French. That’s why I didn’t have trouble moving around: I don’t really have a country that I can say, This is where I belong. What did your parents do?

My father was a geologist. My mother was medical doctor, but she never practiced.

Were you an only child?

No, I have a sister.

Why did you come to France when you were 11?

Because my parents divorced and decided it was good for me to be in France. My mother was German; my father, Swiss-French, from Geneva, just happened to have a German name. I still hope to do a movie in Spanish in Colombia – that’s my dream – but economically it’s very difficult. Also, I’ve got to find a great Colombian writer who is not a friend of Castro. [Laughs.]

Once you were living in Paris, how did you become involved in the movies?

At 13 or 14, I started going to the Cinematheque every night, and also to some faraway theaters around Paris where I could see American movies – sometimes dubbed, but. . . if there was an Anthony Mann movie playing at the Republique, I would go. I was just a cinephile. Cahiers du cinema was like a monthly bible we were all excited to discuss. And then I managed to get closer to the magazine to meet Rohmer. What was/is he like?

Somebody that was very secret. He would never have a phone in his apartment, he would live under another name, he would never have an apartment that had an elevator to go up – he was shocked by people who would use elevators. He would never go to a restaurant or take a taxi – he’d walk or take the subway. So he was very austere, but at the same time very human, very ironic and funny, completely brilliant. The best possible company and the best possible introduction to life and movies. Do you remember when you met?

I came to Cahiers [with the] excuse that I wanted to look at an old issue. He was very brusque: “Oh yes, sure, here, go over in that corner.” He wasn’t very welcoming; he just did his work.

[After that, I’d] sit around and participate in the discussion. Everyone came back at 5 o’clock after seeing the latest movies, and it was like a salon, exchanging ideas about movies. He was behind his desk making a few remarks from time to time, but he was not the type to pontificate. It was a totally free exchange by everybody. So this was extremely exciting.

Didn’t you also write for Cahiers?

Very little – about Maurice Tourneur and Cukor, I think. I was not gifted at writing.

Your biography says you went to the Sorbonne and studied philosophy.

I didn’t go for very long because I went there thinking, Oh, now I’m in the adult world, and they started calling names and checking attendance, and I felt, Oh, I’m still in jail, like in school before. I thought it was going to be freedom, and it was suffocating. Then I met Fritz Lang, in ’58 or ’59, and I wanted to work on a project he had in India. He told me, yes, if you’re there on such and such a date at the studio in Bombay you will be able to work on the film. And I went there, and the door was closed and the movie was canceled, so I ended up spending six months in India anyway. When I came back I worked with Godard a little bit as a [production assistant] on Les Carabiniers.

Had you known him before he made Breathless?

Maybe I met him a few times before. Everybody knew each other. But I wanted to convince the producer, and I did something I always advise people to do when they say they want to be in movies: I borrowed my mother’s old car and went to the production company and said, “I will work for free and I have a car and I can drive!”

You also appeared in Les Carabiniers.

Oh, just one scene. It was nothing, just. . . you have a group of friends, you do a scene, that’s all.

Was it your idea to produce Rohmer’s films, or did he ask you?

It was my idea to start in movies as a producer, to learn. For me, the producer was like a super assistant – somebody who was just helping. I saw an opportunity in helping him when he left Cahiers, in the early Sixties, to produce his two [short] movies, La Carriere de Suzanne and La Boulangere de Monceau.

In fact you really were responsible for Rohmer’s films being produced.

At the time there was a lot of resistance to his movies. I remember submitting those two films to Tours, a very important shorts festival, and they were turned down. It was not that we didn’t get a prize, they wouldn’t even show them, in a film festival that was about movies that were not features. So that shows the kind of desert we were in at the time, as far as recognition of Rohmer. Once he had the success, there was no problem. Ma Nuit chez Maud [’69] was the turning point. [But Maud itself] was extremely hard to produce; I tried for two years.

Where did the company name Les Films du Losange, come from?

Well, it’s a sad story [laughs]. I wanted to call it Les Films du Triangle, like the famous Triangle of silent-era Hollywood, till I found out that Triangle was the name of a bankrupt company. I was having dinner with a writer who said, “Why don’t you take the name Losange? It sounds beautiful and it’s two triangles together – a geometric figure.” I started the production company in ’62-63 doing a third movie, Paris vu par. . . [U.S.: Six in Paris], which was like a manifesto, because the plan was to produce a feature-length film by all six directors.

The episode you appear in, Jean Rouch’s “Gare du Nord,” is remarkable.

It was the beginning of something, and when you’re at the beginning of something it’s always very exciting. This was the first time the new portable 16mm camera with sync sound was used. Rouch had the idea of a movie that would be 25 minutes or so in one single shot, going from the sixth floor of a building to under the wheels of a train.

There must be a cut hidden in the few seconds of pitch black in the elevator.

Of course, we cut there but you don’t know. Not since Rope was anything attempted like that.

Was it Rouch’s idea to use 16mm?

No, mine. I had been working in 16 with Rohmer, but without sound, and we were doing it in two takes maximum. It was the cheapest possible thing in the world, with an amateur camera that you wind up, and post-sync sound. To actually have the movie in the lab only cost a few hundred dollars; then a few thousand more, to blow it up and do the sound. [With] Paris vu par. . ., the double idea was, first, to introduce sound into the 16mm way of working, and [secondly to broaden distribution via] a machine that I thought was going to be revolutionary – you could plug it on a 35mm projector and screen a 16mm print. So we could make a movie in 16, have the prints in 16, and screen it with 35 machines all over France. Unfortunately, when we started trying to use those machines, it was too complicated, it needed a technician to travel around with the machine, so it was totally impossible.

That was the dream behind Paris vu par. . ., to produce very cheaply a great number of auteur movies in 16. The movie ended up being blown up to 35mm, and when you blow up to 35, if you [shot] it in two takes maximum as we did on La Collectionneuse [’67] in 35mm, it ended up being the same price. But two of those episodes really could not have been done otherwise than in 16mm: Jean-Luc Godard’s with the Maysles brothers and their hand-held camera, and Rouch’s.

You produced other films in 16mm, though – Rivette’s Celine et Julie –

– and Le Pont du Nord [’81]. No one wanted to do movies with Rivette anymore, so he devised a movie that wouldn’t need electricity, would be shot with natural light, and the story would be about somebody who could never go indoors. He would choose all the most unusual locations in Paris, so it would be a fantastic movie of a Paris that had never been seen. Those were production elements, those were the givens, and the result is Le Pont du Nord, a brilliant example of filmmaking when you don’t have any money.

Was Rouch an important figure to you?

Yes, very, to me and all the people of the New Wave. One should never forget that the first title of Breathless was “Me, a White Man,” which was an echo, a direct homage to Moi un noir, a very influential Jean Rouch movie.

He seems to have been erased from the history of the New Wave, which drew a lot from his ethnographic film work. Was the story for his Paris vu par. . . episode his idea?

Yes. Basically he said, “It’s the story of a girl who says she wants to dream and escape, and leaves her husband [played by Schroeder], goes into the street after arguing with him, and meets someone who proposes exactly that, and she says no, and the guy kills himself.” He co-improvised the dialogue with us; I don’t remember if there was a writer. I was hoping to do another, feature-length film with him along those lines. He went on doing extraordinary movies in Africa, like Cocorico Monsieur Poulet, and Petit a Petit, [which has] Africans coming to Paris and behaving like ethnographers and filming French people and asking them, “Why do you wear this?” Hilarious, fantastic movies! They’re not known at all.

Another key collaborator you began to work with in the Sixties was Nestor Almendros.

It’s funny, because the link to Almendros was Rouch. Rouch was not only an extraordinary filmmaker but an extraordinary man. Wherever he travels, he plants seeds. He goes somewhere and, a year later, a filmmaker emerges there. Nestor went to him and showed him his movie. Nobody wanted to talk to Nestor because everybody in the French cinema was from the Left and this guy had the worst disease of all: he had escaped from a communist paradise – there must be something wrong with him! Rouch didn’t have a problem with him and I didn’t either, but, believe me, there was nobody who wanted to approach him because the cultural thing of the Left was so strong.

Nestor was living on a camp bed and eating only Quaker Oats, because there was absolutely nothing he could do. I ended up saying to him, “Come to the Rohmer shoot, ‘Place de l’Etoile,’ and do some stills if you like. I can’t pay you.” Then Rohmer had an argument with the cameraman, who was not paid either. Rohmer can be a little exhausting; he walks back and forth and expresses his ideas in a staccato way. And the cameraman got fed up, put the camera on the ground, and left. We were all looking at each other. . . and then there was this voice saying, “I know how to operate those things, I’ve made movies in Cuba.” “You know – really?” “Oh sure.” “Well . . . .” So the next episode of Paris vu par. . .I decided, why not take him? He did fine and everybody loved him and got along great. And then La Collectionneuse was, photographically, a real revelation.

[Rohmer and Almendros’s] relationship was very close; they had the same view of the world, the same aesthetic and the same feeling. We were all learning and discovering at the same time. [Nestor] had done a few things in Cuba, had a few ideas, but they were not fully emerged. It was like witnessing a talent developing.

How did you become involved with Rivette?

Through Cahiers in ’58-’59. Roh-mer didn’t want to spend money going to restaurants, so I would see him during the day and at night I’d go and have dinner with Rivette and Douchet. At one point when my company was doing well, Rivette had a project, Out One, which he had trouble getting made, and I put the money together. I acted in it, I was one of the producers, and I was one of the main people responsible for the seed money.

Out One [’71] was the ultimate experiment in improvisation – improvisation pushed to the max. There was a general structure as always with Rivette, a strategy, but this was his most improvised movie. A lot of the structure was done in the editing. I saw the complete 13 hours and it was exhilarating; it was not boring for one second. The four-hour version [Out One: Spectre, ’73] was a little longer and more difficult. [Laughs.]

What was your role?

One of the people putting out some kind of underground magazine. Each actor was in charge of creating their character, their wardrobe.

How do you produce an improvised film of that size?

You just go by number of shooting days. I would say it was 50 days. That’s not that many.

I know. I don’t think we could have found the money to do more than that. Yet you got to make Celine and Julie.

Usually with Rivette, I would produce a movie of his that nobody wanted to produce, and this movie turned out to be some kind of success, and so he would be able to do a movie with another company, and then this movie was not so much of a success, so then I was there again whenever there was nobody else. That’s my perception; maybe I’m wrong. Whenever it was difficult times, we somehow came up with very little money in a totally desperate way. Somehow we always turned out the best movies.

Were you affected by the ferment of May ’68 and the intellectual climate then?

Sure. You couldn’t avoid it. You couldn’t avoid the belief that you could change things, that this was the beginning of a total revolution, of a new world. You got infected by this collective fever. I think the guy who captured the life and flavor of the times was Jean Eustache in La Maman et la putain [’73], a total masterpiece.

Which you produced for him.

[As with] Out One, I was absolutely instrumental but never put my name on it. It doesn’t matter; the film got made. It was part of the system I had devised for Ma Nuit chez Maud, which was basically $5,000 from ten people, and that $50,000 was the cash to make the movie. The same system of shares was used for Out One, La Maman et la putain, Celine et Julie, and Le Pont du Nord. They all had three things in common: 1) No one wanted to make them. 2) You couldn’t get money from the government, from television. 3) They were obviously masterpieces. All done by asking different production companies to chip in.

So you raised the money from film people.

Film people who had done a movie that had done a lot of money the year before, and for them $5,000 was not a big deal. Claude Zidi [Les Ripoux] helped produce two or three of those. I went to Truffaut, Gerard Lebovcie – an agent who was later killed.

Were you also the line producer?

I made sure there were not too many problems. I was more instrumental in getting them together, but not actually there during shooting. The last time I was line producer was La Collectionneuse. That one, I was working as grip, electrician, everything. After that, I was doing my own movies.

Les Films du Losange still produces movies to this day?

Yes, but now I’m really removed. Marguerite Menegoz runs the company – although I’m sure Rohmer has many things to say also.

Are all Rohmer’s films still produced through your company?

Oh yes, all of them. And there was a German period of Les Films du Losange when we produced films by Fassbinder, Wenders, Werner Schroeter.

Finally, can you reflect on your experience acting in Celine and Julie?

We were doing a little bit of an imitation of Marguerite Duras acting and dialogue. It’s the easiest kind of acting because you’re a ghost – you’re a total fiction [chuckles]. Like all the acting I did in movies I produced, it was to save money, and also just because they were friends asking. I never felt I was making a career as an actor, though I always welcome acting experiences because it’s really very important for a director to experience what it is to be an actor.

So what’s your favorite role?

Roberte [’78], by Pierre Zucca, in which I play three very sexy characters – one is the Marquis de Sade – in some very erotic, weird scenes with the painter Balthus’s brother [writer Pierre] Klosowski and his wife. It was wonderful for me to be in contact with them and to be actually part of his erotic fantasies. All his writings are fantasies about his wife being taken by other men – and I got to play some of these other men onscreen. [Laughs.]

COPYRIGHT 1995 Film Society of Lincoln Center; COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group